From Organize to Win Vol 1 by Jim Britell

“… kids don’t have a little brother working in the coal mine, (or) a little sister coughing her lungs out in the looms of the big mill towns of the Northeast. Why? Because we organized… Those were not benevolent gifts from enlightened management… they were fought for, they were bled for, they were died for by working people…”

– Utah Phillips, labor organizer

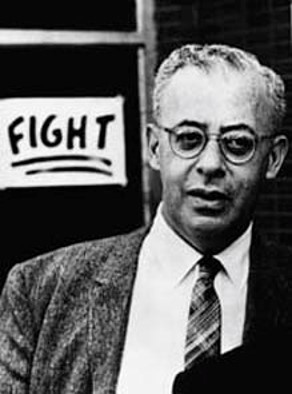

During the 2016 election millions of people from all over the country who had never done any hands-on political activity became politically aroused and are now picketing, demonstrating, letter-writing and calling representatives in every corner of America. Interest in political news is now a national obsession and there is a huge outpouring of interest in income inequality, racism and injustice at every level of society, particularly on college campuses where concern about equality is all-consuming. One might think this newfound interest in politics would be positive for getting people to stand up and fight for their communities, but this is not necessarily so. There is a factor quite apart from outrage that is necessary for concern to result in change, and it was discussed almost 50 years ago by Saul Alinsky just before he died. He gave a long interview to Playboy in March 1972, where he discussed his predictions and worries about the future of America and an example of one of the main things he worried about was demonstrated in a local meeting I recently attended.

The meeting was of local people recently involved in politics because of the Trump election. During the day, local presenters discussed numerous initiatives which had recently been taken to fight climate change and express citizen concern about where the county was going. But every activity that was discussed had one thing in common. Not one required any personal courage to perform. Yes, people were going on buses to marches and demonstrations and showing up for picketing in large numbers, but nothing they had done could ever even remotely cause hard feelings against the organizers or participants personally. When one “works” for climate change on the national or international level, Mr. Carbon Dioxide is unlikely to call your boss and try to get you fired or give you a death threat.

But, as someone who pays attention to threats to communities, I was aware of several planned projects and initiatives which would have a negative environmental impact on their community and region. Talking to the people during a break, it seemed like most people in the room were aware of the problems, but it simply had not occurred to anyone that they could do anything about them. What all the problems had in common was that to do anything about those problems would require the local people to put pressure on elected officials who were their friends, to do things they really wouldn’t want to do to get agencies to change long-established plans, or demand that government funds promised elsewhere in the state be redirected, or suspend the plans of developers or speculators. In short, organizing to oppose them would stir up considerable local controversy and label those involved as “troublemakers” by close friends and political allies.

Most day-to-day activities that build better communities do not ordinarily require personal courage. Sometimes, however, to defend a community’s health, character or environmental integrity, a degree of courage is necessary. Many of the problems of the kind described in this book and the local problems in this community will involve engaging in a degree of interpersonal conflict. And it was just this relationship between effective organizing and the willingness to engage in conflict which was the main concern of Alinsky before he died. In an interview which has now been almost completely forgotten, Alinsky described the problems he foresaw organizers would face when they tried to organize the middle class to fight what he predicted would be a war between large corporations and the rich and everybody else. This article was written before the fantastic engorgement of the one percent took place; when rents in San Francisco and Manhattan were ten percent of what they are now, the average person could pay for college with part-time and summer jobs and incur no loans, and you could pay new baby bills with out-of-pocket money. His insights provide the vital insight which is lacking at the national and local levels today.

In 1972, Alinsky said the next project he intended to undertake was “organizing the middle class, because that’s the arena where the future of this country will be decided.” In his description of what he feared America would become, he said the middle class would become apathetic and terrorized by crime, baffled by computerization, alienated and feel rejected and hopeless. Lacking the ability to participate in the political process, they would become terminally disillusioned. In this state, they would tend towards fascism or radical change. In a bewildered and frightened state, they would grope for alternatives, their impotence and paranoia “…making them ripe for the plucking by some guy on horseback promising a return to the vanished verities of yesterday.”

To organize the disaffected middle classes, it would be necessary to listen to them and eat, sleep, and breathe their problems. Organizers would have to understand and respect them because no tactic or strategy—no matter how shrewd—will succeed with organizing the middle class if you do not first earn its respect and trust. But organizing the middle class would be problematic because the kinds of leaders we would need will be mostly gone. In the past, America created many great radical leaders who would stand up and fight the system, but the McCarthy era in the ’50s destroyed almost all of them. Back then, under attack, the left was too afraid to stand up to the right and turned and ran. This is why young people find someone like Bernie Sanders so original, vital and interesting but those of us in our 70s remember a time when American politics was full of the Bernie Sanders types. In our lifetime, people who looked, talked, and behaved like Bernie Sanders, Saul Alinsky, and Utah Phillips were not uncommon and once whole states and cities were governed by Sanders-types.

So, Sanders is not a new phenomenon; he is a reemergence of a voice once heard frequently. He is only now thought exotic because the earlier generation of leftists turned and ran and left what Alinsky calls a “pitiful legacy of cowardice.” What Democrats were attracted to in the 2016 election was the fire and combativeness of a type of politician who fights for the little guy against big corporations— corporations who care nothing about the middle class.

The heart of what Alinsky said was this: when the fight to restore equity to America begins, we will have to fight for every inch of it against the establishment.

“The liberal cliché about reconciliation of opposing forces is a load of crap. Reconciliation means just one thing: When one side gets enough power, then the other side gets reconciled to it. That’s where you need organization—first to compel concessions and then to make sure the other side delivers. If you’re too delicate to exert the necessary pressures on the power structure, then you might as well get out of the ballpark. This was the fatal mistake the white liberals made, relying on altruism as an instrument of social change. That’s just self-delusion. No issue can be negotiated unless you first have the clout to compel negotiation”.5

Alinsky characterized as “academic drivel” the then-developing notion that consensus and accommodation is the best path to social change. He said he was once asked in a tone of disappointment by a head of a corporation why he saw everything in terms of conflict and not cooperation. He responded that when the corporations dealt with each other with good will and cooperation, he would deal with them that way, too.

In the last election both Trump and Sanders supporters avoided listening to speeches from the other side, so most people did not notice that both promised to fight the banksters, big pharma, hedge funds and Goldman Sachs. Both candidates’ supporters believed they had finally found someone who would stand up for the little guy against the powerful interests which both parties had proven they were utterly incapable of doing. What the American people are trying to say is that at the village and national level, we need leaders who will really fight for the little guy against those now ruling the country.

The current explosion of interest in politics will have to move beyond Facebook to activities that involve politics and projects in our ordinary, everyday, real local neighborhoods. This real involvement should not confine itself to online “virtue-signaling” in search of dopamine strokes from people we don’t know and never meet. We need to find people for local planning commissions, school boards and village councils. We need new local environmental groups to monitor local threats, as well as land-use watchdogs to guard against sprawl and over-development. The government we get at the top will reflect what we can create at the bottom. If local activists can find the courage to fight powerful local interests, national politicians may be able to fight them at the national level, but the change will not start at the top. Our representatives will never do more than faithfully represent their constituents. They are not elected to lead us or teach us, but merely to represent us, so if we want them to show courage at their level, we will have to find courage at ours.

References:

1. David Kupfer, “Utah Phillips Interview,” The Progressive, September 2003.

2. “Empowering People, Not Elites: Interview with Saul Alinsky,” Playboy Magazine, March 1972

This essay is adapted from the conclusion to “Organize to Win” Vol 1 which can be downloaded at britell.com Subscribe to my blog here.